The politics of urban planning and tall buildings at Australia’s Gold Coast

According to Mayor Tom Tate, the Gold Coast is a think-big, can-do kinda place. He says: ‘if you don’t like that, choose somewhere else to live.’ Since Mr Tate and a majority of ultra pro-development councillors came to power in 2012, there has been a litany of abrasive conflicts involving communities and neighbourhoods all over the city. The elected politicians have shown little patience for people who dare to interrogate and protest, or even express alternative viewpoints about council’s urban management decisions. Battles like the destruction of Black Swan Lake, the sale of Bruce Bishop Car Park, and a proposed Cruise Ship Terminal at The Spit have caused deep rifts among, and mistrust in citizens who find they are powerless and ostracised in this political landscape. The issues in dispute can be complex and involve multiple stakeholders, however the most common and protracted battles relate to two major areas of activity: extension of the light rail line, and development of high-rise buildings. Here, I want to focus on the latter - specifically the worrying impacts of unfettered high-rise development and what we need to do to avert a development disaster.

Since the 1970s, the Gold Coast as a holiday destination has traded on the postcard image of the coastal strip marked by tall buildings, framed by the green mountain rim to the west and coastal headlands. Each decade, the skyline has grown up and filled out. When viewed from a distance, it is spectacular and iconic, but when you zoom in close, there are problems.

The Gold Coast council has never been afraid to buck convention, or ignore its own urban development policies. Even before the 2016 City Plan came into effect, the council was supercharging high-rise development. Some of the buildings which were approved in this period and since are colossal to the point of absurd. Already, the areas where redevelopment is proliferating are starting to look and feel alien to the coastal holiday image that has characterised the Gold Coast since mid-last century. Some residents protest at the intrusion of these ‘new kids on the block’. Their disquiet is not just about height. Their issue is with what the planners call ‘plot ratios’, or the size of the site relative to the footprint of the building. These high-rise buildings are going up on tiny sites, creating building densities like never before. It is the symptoms of excessive density that pose most problems for residents. Very dense tall buildings diminish the amenity and character of local areas, and cumulatively, the city as a whole. No matter how expertly designed, they cannot avoid inflicting adverse impacts on their neighbours.

This essay offers urban design perspectives on the policies and politics that influence the shape of the Gold Coast with particular reference to tall buildings - the most prominent and iconic built feature in the image of this city.

Part 1 – SUPER-CHARGED gives an overview of local planning history related to high-rise development, and the key components of the 2016 City Plan that combine to super-charge tall building construction.

Part 2 – SUPER-DENSE identifies the extra yields enabled by this approach and describes the impacts resulting from allowances and liberal interpretation of the 2016 City Plan.

Part 3 – SUPER-GREEN explores solutions for amending the City Plan codes to improve the design of high-rise developments, and proposes a Public Space Landscaping Strategy for Centres zones and the light rail corridor.

SUPER-CHARGED

It is commonly assumed that development of the Gold Coast has been unplanned and is unruly. This is incorrect. This city has been strongly shaped and controlled by town planning policy since its first planning scheme in 1953. Over fifty years, the Gold Coast Planning Scheme evolved through five major iterations (1963, 1973, 1982, 1994, 2003), from a thin set of strict prescriptive rules to a complex scheme which was so voluminous that it was produced on CD for easy access and print cost savings. Community as well as development industry representatives participated in the preparation of the 2003 scheme. Both groups were very mindful of greater public and political expectations for ecological responsiveness, and the State legislative shift towards flexible, performance-based plans. The result was a hybrid approach of prescriptive measures allied to performance standards. After gazettal, in practice, the development industry found the planning scheme was cumbersome and they embarked on a long campaign to unpick, work around and undermine it.

By 2012, when the ultra pro-development Mayor Tom Tate, and a majority of like-minded councillors came to power, there was a mood and mandate for another major overhaul of planning policy in an attempt to ‘cut the red and green tape’. They gave it a more modern, can-do name, the ‘City Plan’, and over four years and multiple drafts, redesigned the scheme so as to essentially deregulate development and supercharge the construction industry. A lot of valuable narrative was dispensed with. Assessment processes were streamlined to speed up approval processes and create more certainty for developers. Local Area and Structure Plans were obvious candidates for omission. But there were many more ‘edits’, and it is difficult and time-consuming to discern the full extent of omissions. Numerous times, I have searched for a specific topic or clause, only to discover that it no longer exists or to find it has been atomised across different parts of a City Plan that has become ambiguous and toothless. If you were to print out and compare the 2003 and 2016 documents, the current City Plan would use much less ink and paper.

The most significant effect of the 2016 City Plan was to exempt most development from Impact Assessment by making it Code Assessable. Developers liked this because it precludes any requirement to give public notice, offers no formal avenue for objections, and denies third-party appeal rights. In theory, the material impacts on adjacent and nearby properties should be responsibly mediated by the council ensuring that development proposals satisfy performance criteria in the zone and development codes. But in practice, this has not occurred. Development assessment reports are packed with jargon and assumptions and extremely thin on rationale. They routinely support non-compliance with code provisions. It is actually unusual for proposals to satisfy any of the code provisions. And despite this, or perhaps because of it, applications are approved routinely without rigorous analysis of adverse impacts on neighbourhood.

Quick development approvals for compliant proposals

It has always been quick and easy to obtain approval for high-rise building proposals that comply with planning scheme provisions. When I began work as a town planner with the council in 1994, the first application I was given to assess was the twin tower Oceana at Broadbeach. It required public notification by a sign on the site and letters to neighbours, only because the applicant sought to exceed the as-of-right 10 storey height limit and build to the maximum 15 storey limit. No objections were received. The large, amalgamated site enabled easy compliance with the set of 16 design standards including plot ratio, site cover, landscaped open space, setbacks, and shadow impacts. We had a multi-disciplinary assessment team which enabled me to obtain prompt checks and advice from transport, landscape, building and plumbing specialists. I wrote the report within a day. It was approved by the planning manager with delegated authority the next day. 18 months later it was built. Having come from Stonnington City Council in inner Melbourne where conservation controls and neighbourhood protection groups can complicate and prolong town planning processes, the pace of approval and development here was exciting. Quick outcomes could be achieved for designated desired development types. From my perspective, the balance of this carrot and stick approach seemed about right.

Podium car parks

The Gold Coast’s high-rise building sector has always been subject to broader economic trends. In good times, the number of cranes in the skyline is touted as an indicator of our booming economy. In the slump following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, there was mounting pressure for the council to remove obstacles and facilitate commercial viability of high-rise buildings.

Developers will always want to extract more profit from their properties and projects. In this case, the council obliged. By the time I returned to the Gold Coast in 2011, after a decade away, summary approval of high-rise development with car parking in above-ground podium decks had begun to happen. Prior to that, plot ratio and site cover calculations had required inclusion of any part of a building above 1 metre from natural ground level. This had the effect of keeping carparks underground to optimise the potential Gross Floor Area for sellable apartments. By relaxing this requirement, the council set a precedent purely to enable substantial construction cost reduction, and a new trend for podium car parks ensued.

Removal of third party objections

Next, developers pushed the potential building envelopes and sought approval for greater relaxation of design and amenity standards.

Their wish was granted with council approval, but which came at a cost to neighbourhood character and amenity. Consequently, this stirred up more objections from neighbours and the possibility of legal challenges, causing uncertainty and delay to the outcomes.

By 2012, when preparation for the new City Plan began, the simple solution for the council wanting to boost the development industry was to make most developments Code Assessable thereby remove any formal opportunity for third party objections and court appeals. The undemocratic and anti-community nature of this decision by an elected council defies belief.

The sky became the limit

And, as if design relaxations and exemption from Impact Assessment didn’t go far enough, the City Plan also reduced developer costs by allowing tall buildings to stand on tiny sites with even greater yields. Plot ratio control and requirements for ground level open space were essentially ditched. Allowances for design levers like site cover, height, and density were increased. This enabled developers to avoid the necessity to purchase and amalgamate multiple properties into a construction site large enough to meet planning and design requirements.

But that’s not all folks. Another significant change was to introduce a Clause 8.2.12 Light rail urban renewal area code that trumps other zone and development codes applicable to properties. This describes a utopian vision for a cosmopolitan transit-oriented living corridor within 800 metres either side of the light rail line. It lists design objectives for buildings that foster ‘street life’ and distinct Gold Coast character. It provides illustrations as examples. There are no rules or even parameters, leaving developers free to push the building envelopes to optimise yield of sites. Most notably, and detrimentally, it encourages towers above multi-level parking podiums, and requires no specification whatsoever of ground level communal open space.

Even the wife of one of the Gold Coast’s most prolific developers expressed concern about excessive development.

Added to this, the entire area from Broadbeach to Main Beach was given an even greater boost with HX designation on the Building Height Overlay Map. This means that there is no height limit, and therefore no trigger for any residential high-rise development application to ever undergo Impact Assessment.

Individually, these are seismic shifts in planning policy. In combination, they spell devastation. Their effect is to render anyone who might feel aggrieved by a development proposal utterly powerless to object, appeal or even influence design improvements. The implications of these decisions for the urban landscape of the Gold Coast in the future, and especially the HX area, are profound.

Policy predicament

Five years on, the impact of the 2016 City Plan is materialising. A new breed of high-rise buildings is going up primarily, but not exclusively, in beachside neighbourhoods. Aesthetically, as individual specimens some of the towers are well-composed and articulated. When viewed from a distance, these buildings are not necessarily inconsistent with height and scale of precedents in their locality. However, when encountered up-close, there is a remarkable difference. They have extremely high plot ratio, density and site coverage. Within the HX area where the sky is the height limit, many are slender as encouraged by the City Plan, but this is only in terms of the height to footprint ratio. They stand like pencils on tiny sites with little or zero boundary setbacks. They intrude indecently on solar access, privacy, and scenic outlook of neighbours. They create cheerless, hard-edged, overcrowded streetscapes that bear no resemblance to the pleasant, vibrant, pedestrian-friendly, cosmopolitan precincts promised by the policy rhetoric.

It is increasingly apparent that, as more of these super-dense building clusters emerge, the cumulative outcome will indeed look and feel more like a ‘Mini Manhattan’ than the ‘Miami Manhattan’ (Gold Coast Urban Heritage & Character Study 1997) coined by Professor Philip Goad for traditional resort-style high-rise urban landscape of Surfers Paradise. If you ask any resident or tourist in the street, they will prefer the resort character with tropical greenery between buildings and interfacing with streets - more like Waikiki than either Manhattan or Miami. Clearly, we have a predicament. Politics and popular sentiment are seriously out of synch.

SUPER-DENSE

The initial step in finding a remedy for any situation is to define the problem. This part of my essay tries to gauge the impact of the ‘extra’ development potential that the 2016 City Plan has allowed by assessing the pros and cons of the developments themselves.

As more buildings of this new Manhattan-style typology are completed, their impact on neighbours and neighbourhoods is becoming increasingly apparent.

In an essay published in the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ Foreground journal, June 2018, I described the traditional character and attributes of Gold Coast tall buildings - and predicted the implications of this shift in planning policy.

As we know, most Gold Coast development applications are Code Assessable and there is no formal opportunity for aggrieved neighbours to object. As a result, 99% of applications are assessed and approved by delegated authority without public scrutiny. Anyone can trawl through the council’s PD Online repository of all publicly viewable documentation pertaining to development applications and assessments, but considerable time and stamina are needed for this. Occasionally, applications for high-rise development come before the councillors for decision in the public arena. You can read the agenda reports and minutes online and watch or review a video stream of planning committee and council meetings. Sometimes, councillors discuss and debate items, which can provide helpful insight into their justifications for approving or refusing development proposals.

In favour of super-dense tall buildings

From review of assessment officer reports and observation of these councillor discussions, I have identified five arguments that are typically put forward in support of applications where a proposed development exceeds performance measures:

More people will enjoy proximity to and views of our magnificent ocean beaches

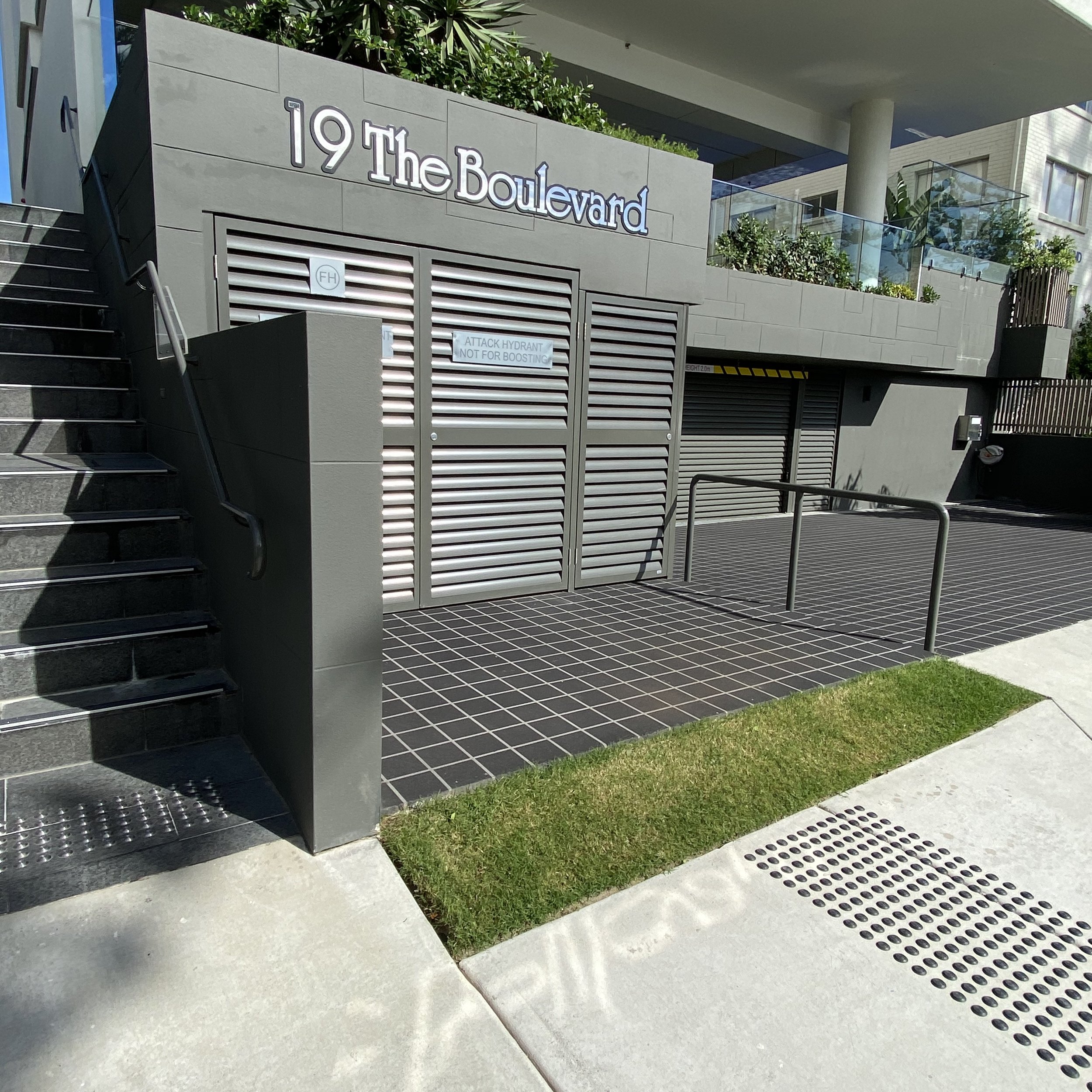

This is a flawed argument based on short-term thinking. From a long-term perspective, allowing a super dense, thin row of tall buildings to line the beach will diminish the amenity and value of properties westwards. Inherent in the previous policy which required landscaped open space at ground level, was the desire to create a natural spacing effect. This enabled new tower positioning to take advantage of views and minimise shadow and intrusion on daylight and privacy. Landscaped gardens and tennis courts provided amenity for residents and contributed to streetscapes, but they were also open space wedges that facilitated an orderly pattern of development, stretching back from the beach in parallel stratum across several blocks. An example of this arrangement is shown here on Broadbeach Boulevard where the open space of Boulevard Towers provided a green wedge for the subsequent tower of Ocean Royale to stand with minimal shadow and enjoy view corridors through to the beach.

Compare this to the new Northcliffe Residences in Surfers Paradise which were squeezed in between neighbouring towers to form a great wall of buildings. This has diminished the views and amenity of existing and future dwellings to the west.

Here is a classic case of ‘you don’t know what you’ve lost till it’s gone’. Defragmentation of the voids that exist by virtue of landscaped open space between buildings only becomes apparent over time. And when the gaps are lost, they cannot be regained.

2. Population growth must be accommodated urgently, as required by the State Government

First, let’s debunk the relentless false urgency for taller, denser high-rise buildings as a means of accommodating population demand. Growth has been a prevailing characteristic of the urban history of this region since the 1950s. When Albert Shire amalgamated with Gold Coast City in 1995, population statistics projected growth of 13,000 new residents per annum. The current annual demand, to accommodate a projected 1 million residents by 2040, equates to approximately 16,500 new Gold Coasters each intervening year. Even if this is exceeded, which is likely having regard to historical patterns, pro rata this growth is not extraordinary and certainly does not require urgent accommodation measures.

It is widely accepted that to sustainably accommodate population growth, the Gold Coast must densify to avoid endless expansion into western and northern greenfields. The 2016 City Plan affirmed pursuance of the consolidation strategy with a defined urban footprint. This is where general agreement ends, and dispute arises around different approaches to managing urban growth.

The planning authorities’ zealous support for densification through high density high-rise development is just one part of what could be a multi-faceted and decades-long solution. There is a glaring gap in demand and supply of affordable medium density and public housing, yet the council doesn’t have a housing policy, or even a statement of intent to address this. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a lot of duplex, townhouse and three-storey multi-unit development which promoted more gradual densification and change to suburban areas. In comparison to the current profitability of high-rise on small sites, there’s little fiscal incentive for developers to bother with this middle ground between high-rise and suburban sprawl.

While high-rise construction is skyrocketing, the Gold Coast Council and State Government could give more than lip service and start actively promoting this ‘missing middle’ section of the housing market. I have previously written about this opportunity. Click on the Mid-Rise Gold Coast image for the link to that.

Another opportunity is to promote occupation of vacant dwellings. In 2016, there were 23,347 vacant dwellings in the Gold Coast. The State and Federal Governments could be facilitating more rental through tax incentives to property owners and subsidies for tenants. As the Gold Coast transitions from a predominantly tourism destination with residents to a lifestyle destination with tourism, the council could collaborate with the higher levels of government to pursue a range of such alternative residential accommodation strategies which will both meet growth needs and deliver higher quality living conditions.

3. Exceeding the Residential Density designation is not a valid ground for refusal

Time after time we hear councillors claim that density calculations pertain to water and sewerage infrastructure charges, and that refusal of proposals for the amenity impact of excessive density would not stand up in court. In discussion at recent meetings, it has even been suggested that there is no legislative requirement for Queensland planning schemes to control density, and like plot ratio, density provisions should be omitted from the City Plan. The argument being that there are alternative techniques for calculating developer contributions and density limits are being routinely and substantially overruled because they are meaningless.

Denial of the significance of density is misleading. The primary purpose of density provisions is to facilitate the orderly development and diversity of residential areas – as well as ensuring adequate developer contributions for urban infrastructure provision. Density is an integral design determinant. It’s a determining factor of the overall bulk and scale of buildings.

When it comes to assessment of building plans, the impact of greater density is not rigorously analysed. Density is a ratio, calculated on the number of bedrooms to square metres of site area.

RESIDENTIAL DENSITIES

The formula is simple, but as an abstracted provision, density cannot be visualised in isolation. Rather, it combines with and manifests symptomatically in a host of other directly visible provisions. When a development proposal is too dense, it becomes evident in other aspects. Excessive site cover, inadequate setbacks, unreasonable overshadowing and insufficient, or absurdly designed car parking that requires mechanical stackers, are all indicators that a building is too dense.

30 storey tower approved for 607sqm site at 59 Garfield Terrace, Surfers Paradise. Density 1 bedroom/3.9sqm

Across all RD designations, the council has been allowing excessive densities. In highest density RD8 areas, the ratio is 1 bedroom / 13sqm of site area. It is common now to see approved densities around 1 bedroom / 4sqm, which is remarkable by standards in any world city. This is only achievable because there is no plot ratio control and the council consciously ignores other design provisions like setbacks and site coverage.

For developers, this triple density is a bonus which translates to huge cost savings in purchase of land, and high profit yields. The council also gains with more infrastructure charges (>$20K per dwelling); and the increased number of rateable properties creates more recurrent revenue. The environmental impacts are greater too. Compared to traditional Gold Coast standards, these super-dense tall buildings cause massive cumulative damage to neighbourhood amenity and microclimate. And neither are they energy efficient. High levels of energy are consumed and embodied in construction. Seldom is solar electricity generation incorporated. Internally, dwellings rely on mechanical air-conditioning. Some bedrooms and bathrooms do not even have external windows with natural light.

In the current political climate, where it seems economic gain prevails over environmental values, and private interests are favoured over public good, there’s little wonder why community calls for re-introduction of density as an Impact Assessment trigger fall on deaf ears. Those in power have removed any avenue for constructive criticism through objection, and won’t even facilitate open discourse on the matter.

4. Tall buildings are slender and cast small, fast-moving shadows

Applicants, assessment officers, and councillors commonly assert that because tall buildings are slender, they cast fast-moving and therefore inconsequential shadows. This is a false argument, as I will demonstrate in a moment. Tall buildings are inherently slender, as a ratio of height to girth. However, when approved on sites little larger than their footprint, they disrupt orderly development of the urban pattern and form and often have detrimental impacts on surrounding properties.

KOKO Broadbeach: 1032sqm site, 32 storeys, density 1 bedroom/4.3sqm, 3m side setbacks. If you imagine the same building form replicating along the street, the future of Elizabeth Avenue looks bleak

Often, these slender, tall buildings do not standout as extreme in the skyline to the casual observer. Take for example the recently completed KOKO apartments in the Broadbeach street where I live. The 32-storey building is slender and looks even meek compared to larger buildings in the locality such as the 40 and 50 storey Oracle Towers to the north. But there is a big difference. It stands on a 1032 sqm site (2 standard house lots). By comparison, The Oracle development covers 11,810 sqm (23 standard house lots). If you contemplate clusters of tall buildings like KOKO, standing shoulder to shoulder on tiny sites, the future is foreboding.

I talk with new residents who walk their dogs and stop for a chat when I am gardening. Most are senior southerners who have bought units where they can enjoy sunny winters. It’s good value for lifestyle. All units have north-facing views and nicely appointed kitchens and bathrooms. They love proximity to the beach and the buzz of Broadbeach. They aren’t really concerned about the long-term future value of their units. They are enjoying it now. They don’t use the communal lap pool or barbeque space on level 4. One new neighbour admitted that the best thing about living in KOKO is that you don’t have to look at it.

When you experience KOKO from the street, the building is brutal and uninviting. It does not provide pedestrian shelter and shade and even in the slightest wind gusts, there is a palpable, uncomfortable downdraught. Setbacks are negligible and there is no landscaped open space at ground level. Aruba Sands Resort to the south is crowded, overlooked and shadowed for most of the day. Presumably, that site will be redeveloped too, but now its potential building envelope has been substantially compromised by the overwhelming form and closeness of KOKO’s tower. Fortunately, the amenity impact on residential buildings to the east and west is not devastating as many residents of Elizabeth Avenue had feared from the architectural renders. However, the too-close three metre side setback of the KOKO tower does diminish the future development potential of the adjacent sites (this is explained in the next section).

KOKO was fortunately positioned to borrow amenity from its neighbours and avoid the need to create amenity onsite. All units have protected views north between the Oracle towers. Residents can also enjoy overlooking the podium-top gardens of Oracle, and proximity to Oracle Boulevard and No Name Lane which cut through that development and provide public space with greenery and high amenity. This was a financial masterstroke by the developer. They made savings on the construction cost because the council required no landscaped open space, minimal communal facilities and common areas. They also saved on the initial cost of the land (around $5K/sqm) made possible because the council allowed all of this on such a tiny site. And as a bonus to enhance sales, common area minimisation enabled the developer to offer very low body corporate levies, capped for the first five years.

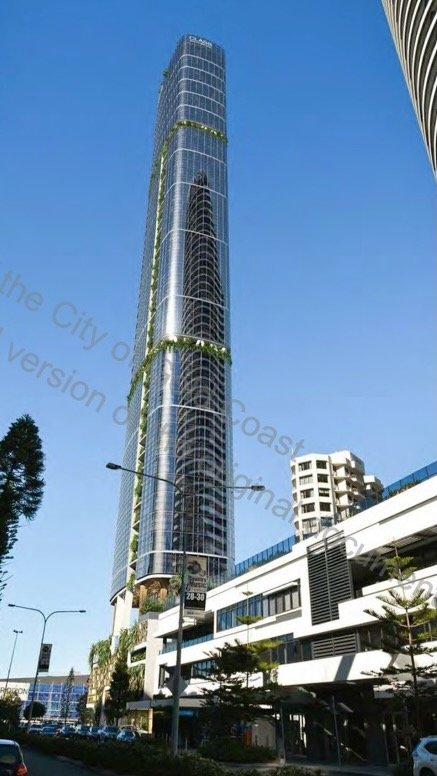

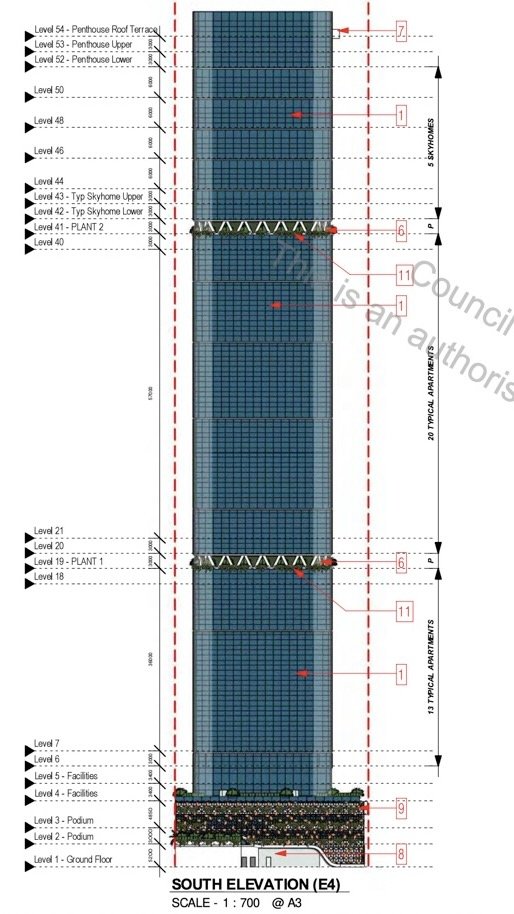

An even more extreme example of ‘tall and slender with fast-moving shadows’ was approved for a 756 sqm site just around the corner, at 2 Charles Avenue. If built, the 54-storey tower to be called ‘Class’ would provide car parking with mechanical stackers and on-site attendants 24/7 because the site is too narrow to construct ramps for circulation. The assessment officer’s report explained that siting of the slender tower floor plate (i.e. stepped in from an intense multi-storey podium) will reduce any perceived dominance, but it’s hard to agree if you look at the pictures. Rote justifications like this are habitually made in support of super dense tall building proposals like this anywhere in the HX and Light Rail Overlay areas.

Here, there was no mention of the visual impacts for residents and guests of the Oracle East tower, or the shadows that will cast fully over their pool and recreational deck for entire mornings. Shadow diagrams are submitted but not scrutinised. Even with Kurrawa Park in between, this 54-storey building, will cast shadow that reaches the beach from early afternoon till sunset. It will be thin with regard to the stretch of beach, but cumulatively, all such shadows are diminishing the open, sunny nature of the coastline which is what attracts settlement here.

Colossal proposals like this are absurd. For the council to approve them is careless and reckless. It’s no surprise there has been a fire sale of units in the Oracle East tower since this decision, or that a scaled down building called Luxe, with 35 storeys, is now being marketed. The height reduction however, does little to lessen the impact on Oracle.

Outside the HX area, the form of most high-rise buildings is different. For example, in construction hotspots like Palm Beach and Labrador, most buildings are between 9-15 storeys. These are not slender from any perspective, but the amenity impacts are also substantial. This demonstrates the equal, if not greater importance of density as a determinant of urban amenity.

5. Green walls and public artworks give street appeal to multi-level podiums

It has become common practice to screen the facades of high-rise developments with podium car parks showing green walls and decorative art. Landscape architects refer to this as ‘parsley on a pig’, a garnish that does little to mediate the domineering podium forms.

Ideally, buildings should integrate three-dimensionally with street level to frame the public realm. They should be shaped to reduce impacts of wind channelling, provide shade and shelter for pedestrians, and safe and discreet vehicle accessways and loading bays. Where appropriate, creation of retail and dining interfaces is encouraged, as are public gathering spaces enriched with landscaping and public artworks.

Regrettably, many shopfronts at the ground level of new buildings are empty and some are occupied by uses that don’t contribute to street vibrancy. Perhaps greater take-up is being inhibited by other financial and leasing constraints. From an urban design perspective, the policy intention for activating the base of buildings with commercial premises is good. I view the vacant shops as latent opportunities, not a blight.

In 2019, the Gold Coast Council published an excellent Urban Ground Guideline to improve design of the first 16 metres of multi-storey developments. This emphatically states that multi-storey podiums are not desired outside the centre areas of Southport, Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach. Although the guideline is not mandatory, a promising trend is emerging as a result, at least in the luxury residential market. Proposed developments like La Pelago at Budds Beach promise verdant tropical planting. In our subtropical climate, undercrofts and balconies like these can be greened with hanging vines that weave together and form canopies above misting gardens. Imagine vines draped between buildings to create green shaded walkways and gathering spaces, like rainforest among concrete jungle.

Clearly, different design approaches to greening are required for tall buildings with podiums and those where the tower extends to ground level. In both scenarios, the presence of gardens and greenery can go a long way to alleviate detrimental effects of super dense, tall buildings.

Problems with super-dense tall buildings

Construction cranes dotting the skyline of the coastal strip indicate that the City Plan has been successful in its intent to supercharge high-rise development. The current count is over 30. They stretch from Biggera Waters to Coolangatta and even inland to places like Robina, Hope Island and Benowa. Our high-rise skyline is becoming even more distinctive, however, closeup, in affected neighbourhoods, many residents are not happy. There are many causes for concern.

1. Absence of ground level open space

Infinity, Surf Parade Broadbeach (under construction)

Developers have been enabled to economise on site area by positioning communal recreation and pool areas on top of several storeys of podium car park, or even at a mid-level floor. This form of development has not been contained to the centres of Southport, Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach as stipulated by the Urban Ground Guideline. Almost everywhere where high-rise buildings are allowed, there is no requirement for landscaped open space at ground level. Added to which, narrow frontages are taken up by gaping driveways, service boxes and garbage receptacles. This is having profound consequences for streetscapes. Outdoor recreation activity is siphoned up to levels out of street view. Without the softening and greening attributes of open space and garden interfaces, or a compensatory strategy to boost street tree planting and parks, the character and amenity of neighbourhoods have deteriorated sharply.

2. Shadow, daylight and privacy

Summit, Frank Street, Labrador

Buildings with negligible and zero setbacks cause greater shadow impacts on all but northern neighbouring properties. Similarly, general solar access for natural daylighting of habitable rooms is reduced. As buildings become closer, personal privacy is compromised by overlooking balconies and windows. There’s a direct relationship here: the more the design relaxations, the greater the impact.

3. Scenic views

It is often argued that you can’t own a view, but outlooks were protected indirectly to some degree by setbacks. Front setbacks, in particular ensured alignment of neighbouring buildings so that one did not obtain a greater advantage than others. When new buildings creep forward substantially farther than adjacent buildings, they steal scenic amenity from their neighbours. By consistently dispensing with setback requirements, gross inequalities in scenic view have proliferated.

4. Wind tunnelling

Tall buildings intensify wind, especially when they are positioned close together. This is because wind speedincreases when air is channelled through a narrow gap. As a general rule of thumb, average wind gusts of up to 5m/second are comfortable and safe for pedestrians on streets. Although it is impossible to design for ideal conditions in every wind direction, there are various techniques that can help to reduce the effect of down droughts at ground level, such as stepped facades, protruding balconies, and awnings. The council does not always require applicants to lodge wind studies, in which case approvals are granted with a condition requiring subsequent wind-modelling, however by then it may be too late to incorporate design changes to avoid unreasonable wind impacts. To experience the phenomenon of wind tunnelling by tall buildings, try walking down Old Burleigh Road past the three towers of Jewel, or the 76 storey Ocean building nearing completion on The Esplanade, even in a light breeze. You will not want to do it again, if you can avoid it.

5. Beach shadows

Introduction of the HX, unlimited height designation from Broadbeach to Main Beach dispensed with graduation of building height controls stepping away from the beach to lessen shadow impacts on the beach. Now that esplanade and beachfront buildings are rising taller and closer together, shadows lengthen and in some places almost join up, casting long stretches of beach into shade. While the Cancer Council may appreciate this, most residents and holidaymakers don’t – especially in winter.

6. Car parking and loading

A common fear of local residents is that new buildings will not have enough car parking spaces and surplus cars of new residents will congest the streets. This does not always happen. Outcomes are variable. Some buildings even provide more spaces than necessary for resident cars. None ever provides enough for visitor cars.

Few new buildings provide loading bays large enough for furniture delivery and removalist trucks, which causes intermittent chaos in some streets.

In some buildings along the coastal strip, especially where apartments are short-term let or used by absentee owners for holidays only, basement car parks are only ever filled to capacity during weekends and peak holiday periods. In other areas, buildings are more likely to be occupied by permanent residents and there are never enough car spaces. Such is the case around the high-rise building clusters near Harbour Town shopping centre in Biggera Waters. Every evening, surplus cars are parked for hundreds of metres along the arterial Oxley Drive. Many of the new super-dense tall buildings are designed with stackers for car parking. These can be problematic from Day 1, let alone faults, breakdowns and maintenance as they age. Numerous tenants of Elysian at Broadbeach, park in the street in case they want to use their cars spontaneously. They say it can take 15-30 minutes get their cars out of the basement parking stack.

There’s a whole urban transformation agenda, not unique to the Gold Coast, in support of public and active transport, autonomous vehicles, working from home, online shopping and the uber economy which should reduce our current need for individual cars and car parking. There’s also the local agenda that couples high-density high-rise development with the light rail project. Unfortunately, because the design of the light rail has degraded streetscapes through areas like Southport and Surfers Paradise, and because the council uses proximity to the light rail corridor as justification for approving grossly non-compliant high-rise development, many residents view the light rail project as a Trojan horse for development uplift and protest against further extensions southwards. This in turn has become a red herring that distracts attention from the heart of the problem, which is poor design of both the light rail corridor and high-rise development in the designated renewal area. And reverting to the salient point about car parking and high-rise buildings, the utilisation of mechanical stacking systems to meet car parking requirements is a clear indicator that a site is too small for the scale of building proposed.

7. Devaluation of adjacent properties

In some circumstances, by allowing zero and negligible side and rear setbacks, the council inadvertently enables developers to steal value from owners of neighbouring properties. Take the case of KOKO at 12-14 Elizabeth Avenue Broadbeach. The adjoining property, Marijan Lodge, at 10 Elizabeth Avenue has a three-storey building with nine units. The land is long and narrow. It stretches across the block and has 18m frontage to two streets. KOKO’s four-storey podium sits right on the shared side boundary. The tower, stretching 100m tall is setback just three metres on both side boundaries.

In the meantime, the council has proposed to refine Acceptable Outcomes for ‘well-spaced buildings’. For buildings greater than 55m in height, the minimum acceptable separation distance from an existing or approved building greater than 33 in height adjacent or on-site is 20m.

I agree with this amendment, but it begs the question – was it appropriate to approve KOKO in the first place, with its grossly reduced side setbacks, just because there is no existing tower or live development application for 10 Elizabeth Avenue? If the standard calculation for side and rear setbacks were applied, the top floor at 95.2m high would need to be set 16.6m of the boundary. However, because this site is within a Light rail urban renewal (secondary focus area), here, three metres was approved. It could be reasonably expected that a reduction to the half share of the 20m separation between proposed and potential future towers might be fair, but three metres is clearly inadequate. The Unimproved Capital Value of the properties at 10 Elizabeth Avenue (and consequently rate charges) have escalated from surrounding sale prices, yet the owners are stuck in the middle with units that are now significantly less attractive for purchase by prospective developers.

8. Piling noise and damage

Effects of piling for construction of basements and foundations has always caused problems. The council allows developers to employ different techniques. The cheapest is sheet metal piling which hammers the foundations into the ground. This technique is commonly used. It causes deafening noise, dust pollution and earthquake-like vibration. Fortunately, the noise and dust are temporary, but with zero and negligible boundary setbacks, the risk of damage to nearby buildings and infrastructure is even greater.

9. Construction disruption

Noise and dust, traffic hold-ups, and workers’ car parking, sometimes over two or three years, are part and parcel of living near construction sites. When high-rise building projects had landscaped open space areas at ground level, construction was managed to enable the site office, cranes and loading to be contained within the site. Without unbuilt space at ground level, super dense high-rise building projects entail an extra level of disruption. Builders need to occupy adjacent streets. Where construction sites adjoin a park or beach, the council even grants permission to occupy them and exclude public users - much to the understandable annoyance of residents.

10. Increased urban run-off

Because super dense high-rise buildings have full site basements, miniscule if any, natural ground is retained. Previous planning schemes required communal ground-level open space and a percentage of deep planting in natural ground. This wasn’t just for aesthetics and recreation. The intent of retaining a portion of all sites with permeable ground was to allow rain to percolate to groundwater, to help maintain groundwater levels and to reduce stormwater runoff loads on drainage infrastructure.

11. Groundwater

Impact of high-rise development also occurs below ground. The wider and deeper building basements are, the greater the interruption to ground water supply. It’s astonishing to see the gushing flows from dewatering of excavated basements. In many streets across the city, massive volumes of groundwater are being pumped into the storm water drains 24/7 for months, sometimes years during construction projects. The groundwater in the sandy soil here under the coastal strip of the Gold Coast is not contaminated like in other cities. It is fresh, perched-lake water so it’s good for watering gardens – which is why many properties have spear pumps. The groundwater supply for properties in Elizabeth Avenue, Broadbeach dried up almost immediately when basement excavation commenced for KOKO. Three years on, it has not yet returned, and residents need to use town water for gardens. Solar powered pump and reticulation systems could capture and divert the expelled water to our parks and gardens if council made this a condition for sites requiring dewatering.

12. Sustainability

There are excellent sources for information to improve the sustainability of high-rise development. Brisbane City Council’s New World City Design Guide entitled Buildings that Breathe, promotes key design elements for buildings that open up to cooling breezes, provide lush landscaping, shade and comfort. Our own council’s Urban Ground Guideline shows how the interface of high-rise buildings in activity centres can be designed better to incorporate greenery and enhance streets and neighbourhoods.

The term ‘sustainable tall building’ can be an oxymoron. If you consider tall buildings from purely architectural and engineering perspectives, they are un-ecological. The Sustainable Tall Building: A Design Primer, 2019 by Philip Oldfield, Professor of Architecture at UNSW explains how even those with high environmental performance, use more energy and materials to build, operate (and ultimately demolish) than low-rise building typologies. In some cities, where tall buildings manifest en masse, inhospitable urban canyon and heat island effects can result. However, from an urban management perspective, high-rise development can contribute to sustainability through achieving more compact urban form. Philip Oldfield says densely built environments can be attractive places to live, work and play if they are integrated with public and active transport, quality streets and green spaces.

At the Gold Coast, where the city is flanked by beaches and the wide, open ocean, it should be possible to avoid, or at least minimise such detrimental effects. In practice, too often we are seeing unsatisfactory results. The environmental performance of new buildings does not seem to be a priority for developers or buyers. If it were, we could expect to see sustainable design features incorporated and promoted in sales and marketing material. The recent new trend for black curtain-glass facades is particularly regressive. It limits natural daylight. It doesn’t keep heat out or cool in. Meanwhile in Vienna, technology has been developed to spray solar cells onto windows so they become a power source of clean, renewable and abundant energy. Experientially, the design of most buildings is myopic. When you step inside, many have lovely entry foyers, but few make really positive contributions to the public realm outside. Several have attempted green walls with varying success but overall, there is a conspicuous absence of greenery at street frontages. This is the worst outcome of super-dense tall buildings – the general absence of softening greenspaces to counterbalance the harsh giant concrete and glass buildings. Even the reinstatement of verges with footpaths and street trees is ad hoc.

13. Short-termism

Finally, a question regarding what could be the sting in the tail. What will happen to these super-dense tall buildings in the long term? How soon will they corrode, decay and become too expensive to maintain? 50, 100 or 200 years? The 17 storey Iluka building only lasted 42 years. The Oriana which was demolished in 2014 to make way for Jewel was even younger. If buildings cannot be preserved in perpetuity and need to be demolished at some point in the future, how will hundreds of owners regain fair value from the tiny parcel of land that remains? I have no answer for this prospective dilemma, but it warrants consideration and discussion now.

SUPER-GREEN

Things we love most about the Gold Coast

It can be thrilling to live high above the ground with views of the ocean, city, and/or distant mountains. Many of the new tall buildings promise an elevated level of luxury and, architecturally, some are lovely. However, it must be remembered that no-one comes to the Gold Coast because of the high-rise buildings. The primary attraction, for residents and tourists, is the resort lifestyle within the convenience of an urban setting. People choosing to live and holiday at the Gold Coast are seeking sun, fun and a more relaxed pace of life. Many also want a cosmopolitan vibe without the accompanying crowded, daunting and hectic city like New York, Shanghai, or Sydney. The things people love most about the Gold Coast are blue skies, expansive views, proximity to the magnificent ocean beaches and the lush greenery of nature. And these are the essential qualities which must be protected amid all urban development.

Whose views matter?

Rapid urban growth creates tension and often conflict. Amongst Gold Coasters, there is a broad spectrum of views as to how their city should develop.

State Government

The Department of Planning oversees planning for regional growth and provision of infrastructure. In Queensland, while the State has an interest in increased urban development as the collector of taxes and stamp duties on transfer of land, its Department of Planning has traditionally avoided intervening in design matters at the local level, delimiting its influence to State Interest matters and procedural gazettal of planning schemes drafted by local councils.

Mayor and councillors

The council is the body responsible for ensuring orderly and proper development. Local government also plays a role in promoting growth for the city’s economic prosperity. Councillors understand very well that, in addition to boosting the construction industry and employment, more apartments also equate to more rates revenue, and that judicious management of the council budget augurs well for their re-election. Most current councillors are proudly business-oriented and inclined prioritise economic over community and environmental interests.

Council officers

Planning staff play an advisory as opposed to decision-making role in strategic planning to undertake studies and prepare policies. In statutory planning, they have considerable delegated authority to approve development applications that generally comply with the City Plan. Only a small number of development applications are reported to the councillors for decision. Typically those relate to major developments, applications that have received formal objections, or if a divisional councillor makes a request for an application to be considered by the planning committee. Planning information and communication is tightly controlled and mostly online. It can be difficult for people outside the administration to follow and understand proceedings.

Developers and consultants

While building quality and styles differ, all developers and their consultants have a single aim: to achieve maximum financial profit from their properties and projects. They push boundaries to design and construct buildings for optimal and quick return. They want their buildings to look attractive chiefly for marketing and sales purposes. Care for externalities like the impact on neighbours or street enhancement works or planting is never a priority for them.

Builders, trade contractors and suppliers

People associated with the development supply-chain are most interested in the employment and financial opportunities generated by construction. They tend to favour pro-development policies, and councillors.

Property marketeers and commercial news media

They stoke the pro-development narrative and boost each new project with superlatives. The Gold Coast Bulletin and Channel 9 local news frequently present residents who voice concerns or alternative views as anti-development naysayers.

New residents/investors

By the time property settlements occur at the completion of construction, most local conflicts will have already played out. New residents/investors who have been attracted by the relative affordability and coastal lifestyle value compared to capital cities, will be unaware of neighbour objections or resentment. They are preoccupied with the interior design of their apartments, enjoying the novelty of their new base, and becoming acquainted with the neighbourhood as they encounter it.

Tourists

Maybe it’s time for the Gold Coast to care less about what others think, and stop regarding tourism as the primary driver in shaping urban form and infrastructure? A better strategy could be to concentrate on making this city the best it can be for locals, confident that tourism and investment will follow as outsiders want to be a part of it.

Existing residents

Gold Coasters generally support urban change and have a high tolerance for development. However, residents in renewal areas are becoming increasingly aggrieved by the adverse impacts of adjacent development. Many feel powerless to protect the amenity of their homes and the character of the neighbourhoods they love. They feel that the council is facilitating excessive development, and ignoring community concerns. They are concerned that the growth is misguided and want the council to restore balance before the essential qualities of the Gold Coast deteriorate beyond redemption.

Discontent with the 2016 City Plan

In early 2019, after several years of experiencing genuine and serious concerns about Gold Coast planning and development matters, fifteen community groups joined up to form the Community Alliance Inc. Their mission is to uphold and sustain the Gold Coast’s iconic environmental, cultural and lifestyle amenity values, while ensuring the transparency and accountability of our elected officials’ governance. Several months later, the council proposed a major City Plan update addressing a range of issues. I responded to this update solely on the topic of high-rise building design, as the issue that has troubled me most in recent years. In the first round of consultation, I submitted a request for reintroduction of Impact Assessment triggers for high-rise buildings - namely site cover, density, front setbacks. Preferring to stay remedy-focused, I didn’t even mention the most effective lever of change in this context, plot ratio. Within the second round of amendments, the council proposed to add site cover as an Impact Assessment trigger, in order to achieve ‘balance between built form and landscaping’ – but only in the new medium-density Targeted Growth Areas. In my mind, this amounted to recognition that the current City Plan, or at least implementation of it, was and still is failing to achieve balance, and that the site cover trigger should be applied across all areas of the city where high-rise development can occur. A copy of my submissions is accessible here. Readers will not be surprised to learn that, in the face of the development industry’s strong written opposition to site cover and/or density triggers, I have since moved on to other approaches.

The problem of over-sized buildings on tiny sites could also be addressed by introducing a minimum lot size trigger. It is widely regarded that at least 20 metre frontages are required to accommodate a driveway and separate pedestrian entry, including space for services like fire hydrants and rubbish bins. Most cities stipulate a minimum frontage plus a sliding scale for site area to the number of storeys. For example, 800m² up to 5 storeys, 1000m² up to 15 storeys and 2000m² above 15 storeys. This wouldn’t rule out smaller sites or taller buildings, however development applications exceeding these minimums would need to go through Impact Assessment.

Yet another approach to remedy the problem could be the insertion of a clause that triggers Impact Assessment if any aspect exceeds more than a measurable 10% or 20% departure from compliance with the specified provisions in the high-rise accommodation design code. This sensible suggestion has been made frequently but not picked up by iterative drafts of the update package.

By the fourth and final version of City Plan Updates, it was evident that the council officers had valiantly attempted to address many of the issues raised in the thousands of submissions they received. The changes are too numerous to list and explain here, but the key revisions to high-rise development include:

The light rail renewal area overlay code has incorporated some elements of the Urban Ground Guideline, plus greater definition around tower setbacks and separation distances.

The building height overlay map was amended with reductions for several areas like Jefferson Lane, Palm Beach, Burleigh Heads central area, and Chevron Island where the limited carrying and engineering capacity necessitated scaling back.

The High and Medium density residential zone codes have been revised to promote responsiveness to local character including landscaped open space at ground level.

The high-rise accommodation design code has been tweaked to promote less dominant podiums and more space between towers.

These amendments go some way to appeasing resident concerns by softening the sharpest amenity impacts, however, their impact in reality is minimal. They tinker with the status quo and pussyfoot around the root causes of bad design. They allay developer concerns by avoiding anything that might slow down the development approval process or reduce potential development yields, such as stricter or definitive performance measures. Even so, two years on, the City Plan amendment process has not been finalised. In a letter to a member of the public in September 2021, the Chair of the Planning Committee, Cr Caldwell, advised that the council has not formally lodged the amendment package yet because the State Planning Department has asked for further information on several items.

Meanwhile, the council continues to churn out approvals for colossal development proposals. Many of these are speculative, for the purpose of elevating land values. Some are in areas not previously prone to, or designated for, high-rise development. Developers and sales agents urge property owners to sell before the City Plan updates come into effect and deflate the market, while simultaneously encouraging buyers to get in quickly before the supply runs out. The situation is best described as a stalemate. There is an imbalance between built form and landscaped open space, yet the people charged with responsibility for sustainable urban management don’t have anything adequate in place, never mind the political will, to fix it. While high-rise development is allowed to continue on the current trajectory, the potential to achieve a truly equitable, sustainable and beautiful Gold Coast diminishes.

Super-greening the city

The 2020 re-election of Mayor Tom Tate and his allied majority of councillors who have promulgated this super-dense approach to development, may suggest that most Gold Coasters are happy with what’s been occurring, or are at least indifferent. If this is true, and the community doesn’t feel or exert any pressure, then the situation is unlikely to change.

My intent here has been to assist readers in understanding the issues, the immediate impacts, and the long-term implications of continuing on the current course. I have also offered some ideas on how to correct that course, should the will exist.

When thinking about complex urban issues, I find it useful to start from the premis of the seminal text of Site Planning by Lynch and Hack, 1984, which says, ‘One must know the parts before one can play the game, and the name of the game is to provide human beings with places that support their daily lives, delight them and let them grow.’

The game here is Better Urban Design. Like chess, success requires clear rules and a game strategy. There can be infinite permutations, but it is possible to win with a few smart moves. The council holds the strongest pieces but they don’t appear to have a game plan. I would like to suggest a super-greening strategy involving complementary public and private efforts. Imagine an urban forest amongst the concrete jungle. The council could deliver public landscape works to supergreen our centres, streets and parks. It could also re-introduce a requirement for high-rise residential development to provide ground level gardens. In our fertile subtropical climate, where plant growth is vigorous, the rewards of tree planting and garden cultivation will come quickly. In these two bold moves, enormous improvements could be achieved.

1. Greener centres, streets and parks

Cooling, softening, living greenery under the Grey Street railway bridge in South Brisbane

In a recent essay about re-enchanting Surfers Paradise, I mentioned the opportunity to re-green the streets and parks and gardens with indigenous rainforest species to create a new, leafy, subtropical urban environment. Even the most heavily paved space can be transformed effectively using urban landscape products like City Green, which frames and vaults soils to protect and enable deep and extensive tree roots to grow without damaging building foundations, drains, conduits, paving or kerbs. Proper preparation of the underground will incur greater installation cost, however, if planned and designed carefully, trees will live long productive lives and preclude the need for constant streetscape renewal works.

All of our urban centres as well as the light rail corridor could be super-greened in this way. Imagine what wonderful environments could be created by a City Greening Plan for each of these high intensity activity areas. This would undoubtedly re-establish the resort character that the Gold Coast was famous for. Moreover, if the council takes greater care of public spaces, private property owners are more likely to match the effort with complementary landscaping treatment at the public/private interface.

2. Ground level gardens

Just a decade ago, developers would have never even proposed a high-rise building without landscaped open space at ground level, except in the very central areas of Southport, Surfers Paradise, Broadbeach or Coolangatta. The absence of gardens from recent developments is an abominable trend that should cease.

Like a glimmer of hope, City Plan amendments proposed for the residential zone codes include reintroduction of ground level landscape areas as Acceptable Outcomes. To have any real effect, this must go further and be mandatory, except in the Centres Zone and Primary and Secondary focus areas of the light rail urban renewal area, where the Urban Ground Guideline applies, and the council implements a City Greening Plan.

The Surfers Paradise Marriott Hotel’s garden is big drawcard. New developments are unlikely to provide such expansive landscaped open space, but this shows how living greenery enhances the destination.

The shape, size and location of landscaped open space should be the starting block from which architects generate building designs. It won’t solve crowding, shadowing and overlooking impacts on neighbours in all situations, but the spatial void of a garden creates opportunities for responsive design around it to alleviate building impacts and preserve views through and over it. The garden itself should be well-designed with useable dimensions, open to the sky, at grade with and visible from adjacent streets, and planted with species that will thrive in our subtropical climate. Gardens enhance streets and increase the sales appeal of developments. Of course, dedicating 20-25% of the site area to landscaped open space will cause some decrease of development yields, but this is necessary and urgent and should never have been abandoned.

Super-dense, Manhattan-style buildings don’t suit this city. For a resort vibe with vibrant and beautiful streets, the Gold Coast needs to retain separation between the towers of concrete and glass, and to fill the spaces in between with the softening greenery of living plants. The best solution is green wedges, physically and metaphorically, to bring back some balance in this coastal urban landscape. And this isn’t just for ourselves, we need to do this for people in future generations because if the current trajectory continues, the long-term outlook is bleak, if not apocalyptic.